Serge Mouret

is the son of Marthe Mouret (nee Rougon) and François Mouret, son of Ursule

Mouret (née Macquart); meaning he has both Rougon and Macquart bloods running

in his vein. Serge has two siblings: Octave (who is most Rougon than the others—appeared

in The Ladies Paradise and The Conquest of Plassans); and Désirée,

a retarded girl, of whom Serge took under his care.

Like all the

tribe members, Serge possesses a certain obsession that is in religion; and so

he becomes a priest. He practices total obedience in celibacy and fanatic

devotion that leads to mysticism. He intends to cut off any link with the

world, and to focus more in his devotion, he requests to be placed at Les

Artaud, a remote rural village inhabited by peasants with incest relationship,

poverty, and ignorance of religion. At first Abbé Mouret lives tranquilly by

drowning himself in total devotion. But abandoning his physical health, he gets

ill and loses his memory. A girl who loves to roam in The Paradou, a huge

neglected garden, nurtures Serge under instruction of Doctor Pascal Rougon

(Serge's uncle). Serge regains his health, but forgets that he is a priest,

falls in love with Albine, and even makes love with her under a 'forbidden'

tree. Yes, this is a replica of Adam and Eve's Paradise!

This book has

so many interesting layers to discuss. I'll try to break it down to several

points.

Nature v Church

The battle

between nature and church is the main subject of this book. Zola portrayed the

Catholic Church as empty, gloom, and dead. He especially disapproved of

celibacy, which he believed to be unnatural, because procreation is human's

nature. I learned from the Introduction (by Brian Nelson—one of Zola's experts)

that when Zola wrote this book, France's birth rate was declining. Maybe this is

his critic to the Church, because Zola always believed in fertility.

From the

beginning of the story, Nature has tried to invade the Church—sun enters and

takes possession of the whole church; sparrows fly into the Church through

holes on the window panes; strong farmyard odour enters from front door (the

farmyard is managed by Desiree, and is located next to the Church). But the

biggest battle of Nature v Church is when Albine seduces Serge. Who wins the

battle? As much as Zola liked the Nature to triumph, I think, by making Serge

finally triumphs over his sexual desire, and returns to God, Zola has

involuntarily given the victory to the Church. *spoiler alert* Although Nature

could not be stopped in thriving into Church (Albine's death is taking place at

the same time as the birth of Desiree's cow), Nature still cannot fully conquer

Church.

Sin and repentance

Maybe this

is not Zola’s intention, but this book made me think a bit about sin and

repentance. After his memory returns, at one point, Serge feels that God

abandons him (right after he feels proud of his own purity). He then succumbs

to Albine's invitation, and goes to Paradou to meet her. But when Albine

seduces him (taking him to the Forbidden Tree), God guides him again, and he

can finally cut off his passionate love to Albine forever. Maybe, when we

become proud of ourselves, God deliberately sends us temptation to make us

sinned, and is therefore humbling us and making us worthy of salvation.

|

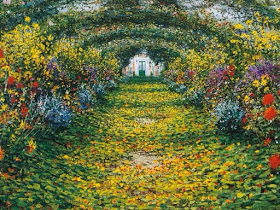

| Le Paradou by Edouard Joseph Dantan, 1900 |

Naturalism and Research

Judging from

the book's main topic, you can surely find naturalism flows abundantly throughout the book. There was a passage where the plants and flowers became alive and at war, attacking the Church! Of course, it's an allegory, but reading it, I felt like I saw it myself! Later, Zola's vivid picturesque narration inspired at

least two impressionist paintings: Le

Paradou by Edouard Joseph Dantan is one of them. And Zola put big efforts

too into his research for this book. He must have analyzed and studied many

horticultural catalogues to present so many plants and flowers throughout the

book that at one point really bored me! And he has certainly studied the Bible,

Catholic Missal, and many devotional books to write vividly of Mass and

Sacramental events in great details.

Women, Immorality, and Misogyny

I was quite

intrigued by the misogyny level in this novel. Brother Archangias--another

religious in Les Artaud (but not ordained?) has a deep hatred towards women; so

much that he thinks 'it would be a good riddance if girls were all strangled at

birth'. Can you imagine this kind of man being religious?

Les Artaud

is actually a tribe, which at the end named the village. Les Artauds people

married their own relatives for ages. They are low in morality, and don't go

into religion. When girls get knocked up, their concern is only of the loss of hands

to work the farm, not of the ruined reputation. Again, getting pregnant means

procreation and fertility...

On the other

hand, when Serge fell into temptation, I felt that the narrator puts the blame

to Albine (the woman brings down the man | woman is temptress); while in fact,

both consciously wanted it. It's not the only example, there are several

incidents throughout the book. I just wonder.. whether it's a common view in

19th century; or is it a vague evidence that Zola is a misogynist?

The Hereditary Illness

Although

becoming a priest, Serge does not devoid of sexual passion. It is through his

fanatic devotion and mysticism that he satisfies himself (he adores Virgin Mary

as his mistress). It makes sense that, when he loses his memory, his sexual

passion reborn through his exposure to the Nature. After his repentance, he

switches his devotional focus to God, instead of Mary. Once again, Zola

'proved' his theory of hereditary illness. Could anyone in the family skip it?

We should know after Doctor Pascal's final investigation is complete... on the

last book: Doctor Pascal.

Meanwhile...

4,5/5 for The Sin of Abbé Mouret.