👑 Genji is the Emperor Kiritsubo's son with his favorite but low ranking concubine from Pauliwnia Court, whom he loved more than the others, more, even, to his wife, Kokiden. The little son was a prodigy (handsome, intelligent, and very talented). And the Emperor would have liked to make him royal prince, but decided not to, because a boy without high rank maternal backing would be tortured by court political backlashes. That was exactly what his mother had experienced (and presumably the cause of her premature death, which caused sadness to the Emperor). Therefore he was brought up instead as a commoner, named Minamoto or Genji.

👑 I couldn't help thinking how lonesome it is being at the top. When one loves a person, the loved one would be hated by others, thus one just causes only grieves to the loved one. Then both would be unhappy.

"Happy are they whose place in the world puts them beneath such notice!

The great ones of the world live sadly constricted lives."

👑 Don't quite understand too why parents at that era (most often the father) thought that sending their daughters to the court would make them happy. But then, that's typical of Asian parents, apparently - telling their children to be so and so "because they know what would make the children happy", while ignoring what the children must have thought for themselves.

👑 And it's also typical of Asian children to obey their parents. Disobeying means disaster, but obeying often leads to another disaster. And it's amazing how generation after generation repeat the same thing, while they know the consequences.

👑 Anyway, a princess called Fujitsubo, whose resemblance with Genji's late mother is uncanny, was brought to the court and won the love of, not only the Emperor's, but also young Genji, despite of his (Genji's) recent marriage with the Minister's daughter (political marriage without consent of neither bride nor groom), right after his initiation as an adult.

👑 By the second chapter, it is clear that Genji is a womanizer, and that the whole story would center mainly on his numerous amorous adventures. His interests extend from young girls to older women, from high rank princess to girls from far lower rank. Of all his women, he respects his wife most, but there's not warm affection from both sides.

👑 Though disapproved of Genji's immorality, I was prepared to tolerate it, as it was the imperial's way of life at the 11th century. However, when he took a beautiful little girl of ten y.o. to "shape" her to resemble Fujitsubo (whose love he cannot have) and to be his future wife; well...I lost a little respect I've reserved for him. Even the little girl's people thought it inappropriate.

👑 I was relieved then, that he kept his promises, to treat Murasaki (the little girl) more like his protegé. She continued to be his favorite lady, though it didn't prevent him from having an affair during his exile - which, by the way, was the result of his other scandalous affair with the Emperor's consort. In short, the tale is about Genji's love affairs, with a little glimpses of court politics at that period, composed neatly with lyrical poems and prose.

What I loved most about this book:

❤ The Poems - I quote one here for you:

"The lady was sad, and more beautiful for the sadness, as she recited a poem:

'They say that it is dawn, that you grow weary.

I weep, my sorrows wrought by myself alone.'

(Genji) answered:

'You tell me that these sorrows must not cease?

My sorrows, my love will neither have an ending.'”

❤ The art of communications - carefully chosen paper colors and materials for letters, implying different meanings; the handwriting and gradations of ink, intensifying the writer's feeling. Sometimes they exchange fans with some handwriting on the corner.

❤ The musics - They play koto (eight or thirteen strings instrument) and flute, and the best players often brought tears to the listeners. I could well imagine the beauty of such musics. The sounds of Japanese or Chinese Koto and Flute, or Indonesian gamelan, always bring peace into your soul.

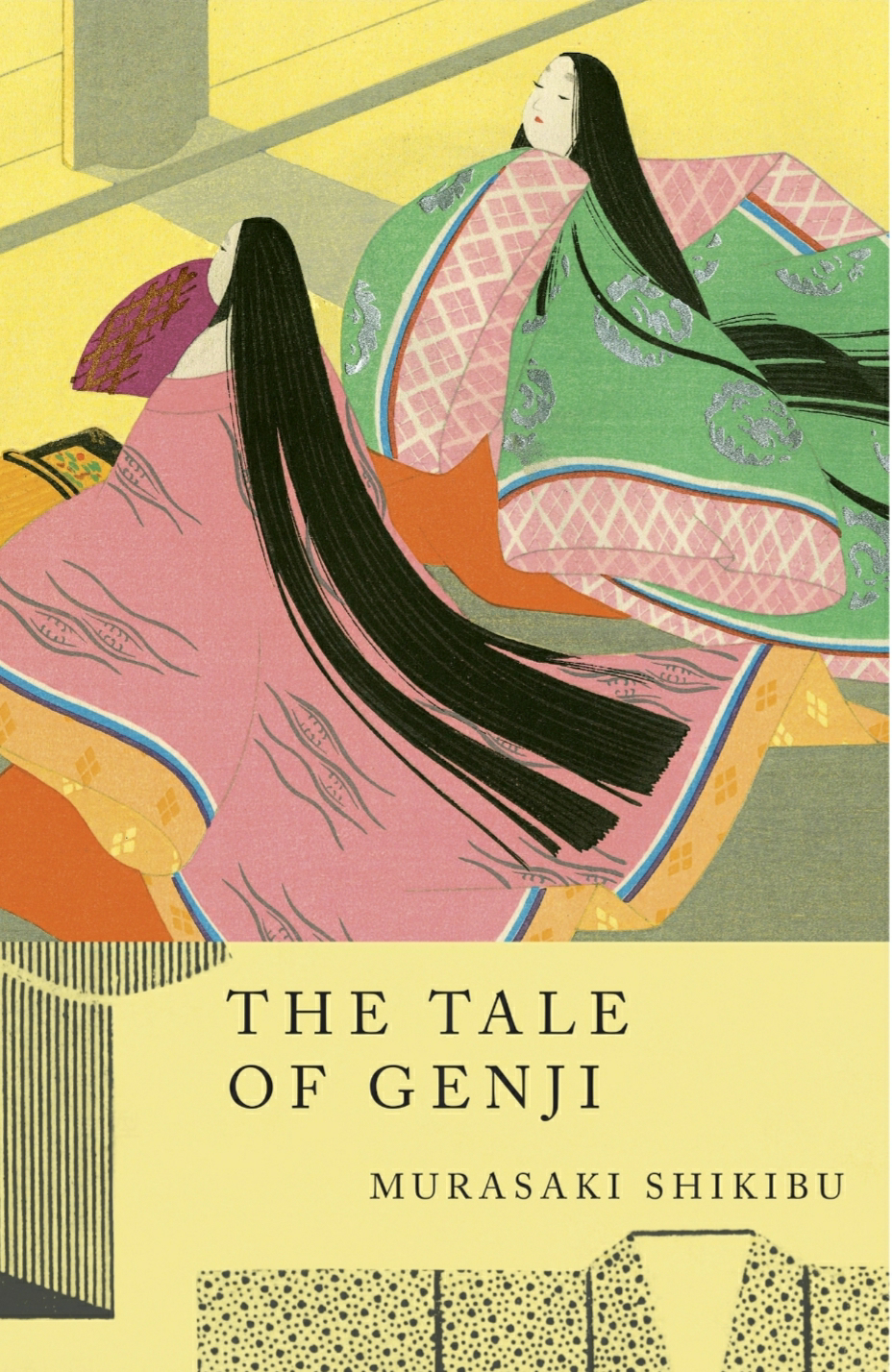

👑 Tale of Genji's original manuscript actually composed of fifty four chapters. The one I read is the abridgment, of Edward G. Seidensticker's translation, containing twelve chapters. I've randomly chose this version, mainly because its availability on Google Playbooks. But after small researches through google, I'm glad I'd pick this up in the first place - it's considered quite following the original rather strictly, but not too scholarly to cause you headache. 386 pages of Genji is the perfect dose, I guess, and with all the beautiful poems along with prose, one can follow nicely the tale.

If you need more references to which translations to pick, check this blog's helpful and thorough comparation of half a dozen versions of Genji's.

👑 The only setback is its inconclusive ending. But again, I didn't feel like reading further of Genji, so I guess, this is it. It's worth to read for its literary value and classic beauty, but not more.

Rating : 3 / 5

I read this book for Japanese Literature Challenge #15

This is one of my favourite novels for its depiction of life in Heian Japan (or at least for the aristocratic classes), but you are right: when I reread it recently, I got very annoyed with Genji especially in his younger years. My favourite bit is right at the end - the Uji chapters, after Genji's death, because I think it shows his legacy across generations, but is much more thoughtful and melancholy. I also wrote a post comparing the different translations, and I may be one of the few people who prefers the Seidensticker translation, as being more manageable, more pleasant to read.

ReplyDeleteI wonder which version of Seidensticker's you read (are there more than one?), because my edition ended in ch. 12 (when Genji started to be favored again at the court after the painting competition). I don't know why Seidensticker didn't decide to continue through Genji's (or even Murasaki's) death, but I'm glad I've decided to read it anyway in the first place.

DeleteThis is a classic I have always been meaning to read, but never have. I liked the way that you broke it down for us in your review, giving the highlights and interpretations. I especially liked the ways that Asian parents and children relate…even though I am not Asian, I have been quite obedient, and that has always worked for our family! Thank you so much for reviewing it and participating in the Japanese Literature Challenge 15!

ReplyDeleteThis was rather a chore to read. I'm glad to have read it...an exposure to Eastern Classics...and even though I lived in Japan, I think much was lost, on me.

ReplyDelete